Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) is one of the most important — and most misunderstood — cost drivers in Bitcoin mining.

In this article, you will learn what PUE measures, how infrastructure overhead silently increases electricity costs, and why two mining sites with identical power prices can have different profitability.

If you are modeling mining economics, evaluating hosting offers, or building mining infrastructure, understanding PUE is no longer optional.

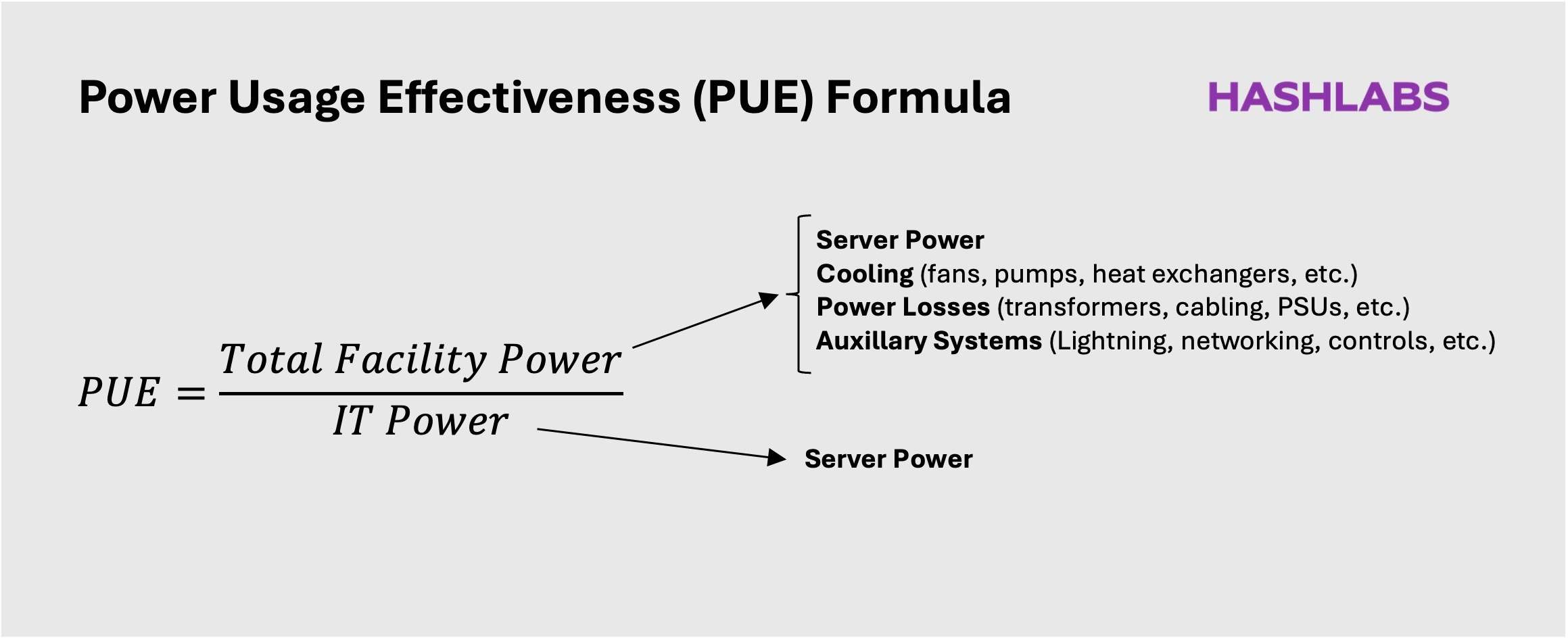

PUE measures the ratio between the total electricity consumption of a data center and the electricity consumption of the servers within that data center.

To calculate PUE, we simply divide Total Facility Power by IT Power.

Total Facility Power comprises all electrical loads in a data center, including servers, cooling systems, power losses, and auxiliary infrastructure. IT Power, on the other hand, represents the pure electricity consumption of the servers themselves. We will describe these components in more detail in the next section.

A data center’s core function is converting electricity into compute as efficiently as possible. As a facility owner, you want to maximize the share of electricity that directly produces revenue-generating compute — not power spent on cooling, auxiliary systems, or electrical losses.

PUE is therefore a highly relevant metric, as it directly measures the energy efficiency of a data center. The closer the PUE is to 1, the better.

In most traditional data centers, PUE ranges from roughly 1.10 to 1.50. Bitcoin mining data centers tend to operate at lower PUE levels due to intense cost competition. In mining, typical PUE values range between 1.03 and 1.20.

To illustrate the concept, consider a mining facility drawing a total load of 100 MW from the grid. If the mining machines consume 96 MW, while the remaining 4 MW is used for cooling, power losses, and auxiliary systems, the PUE is calculated as:

100 MW / 96 MW = 1.04

In hyperscale data centers, PUE is treated as a core operational KPI. In Bitcoin mining, however, it is rarely discussed — despite the sector being significantly more cost competitive. As mining converges with the broader data center industry, PUE will likely become a standard operational metric across all large mining facilities.

In the next section, we examine the components that make up PUE in more detail.

As discussed, the numerator in the PUE equation is Total Facility Power. While most power consumption comes from mining machines, the remaining share stems from three primary sources:

After producing hashrate, virtually all electricity consumed by mining machines is converted into heat. In our previous example, a 96 MW IT load generates 96 MW of heat — an enormous thermal output that must be managed to prevent overheating.

In most climates, this requires active cooling infrastructure such as:

This equipment consumes significant electricity without directly generating revenue.

Cooling demand is highly climate dependent. In scorching environments like the Arabian Peninsula, a large share of facility power must be allocated to cooling. In colder regions such as Norway, cooling requirements are far lower.

An important implication is that a low electricity price in a very hot region can end up being less competitive than a slightly higher price in a cold region due to additional cooling overhead. This dynamic is one of the primary reasons the Nordics have become a major Bitcoin mining hub.

Electricity entering a mining facility travels through multiple stages before reaching the servers. Along this path, some energy is lost — referred to as power losses.

These losses occur across electrical infrastructure, including:

The largest share typically occurs in transformers. Modern high-efficiency transformers often lose roughly 0.5–1% of electricity per pass-through. Since mining sites commonly use two transformer stages, total transformer losses alone can approach ~1–2%, with additional minor losses elsewhere in the system.

Auxiliary systems include:

While individually small, these loads create a persistent overhead that must be included in total facility consumption.

With a foundational understanding of PUE, we can now examine its economic impact.

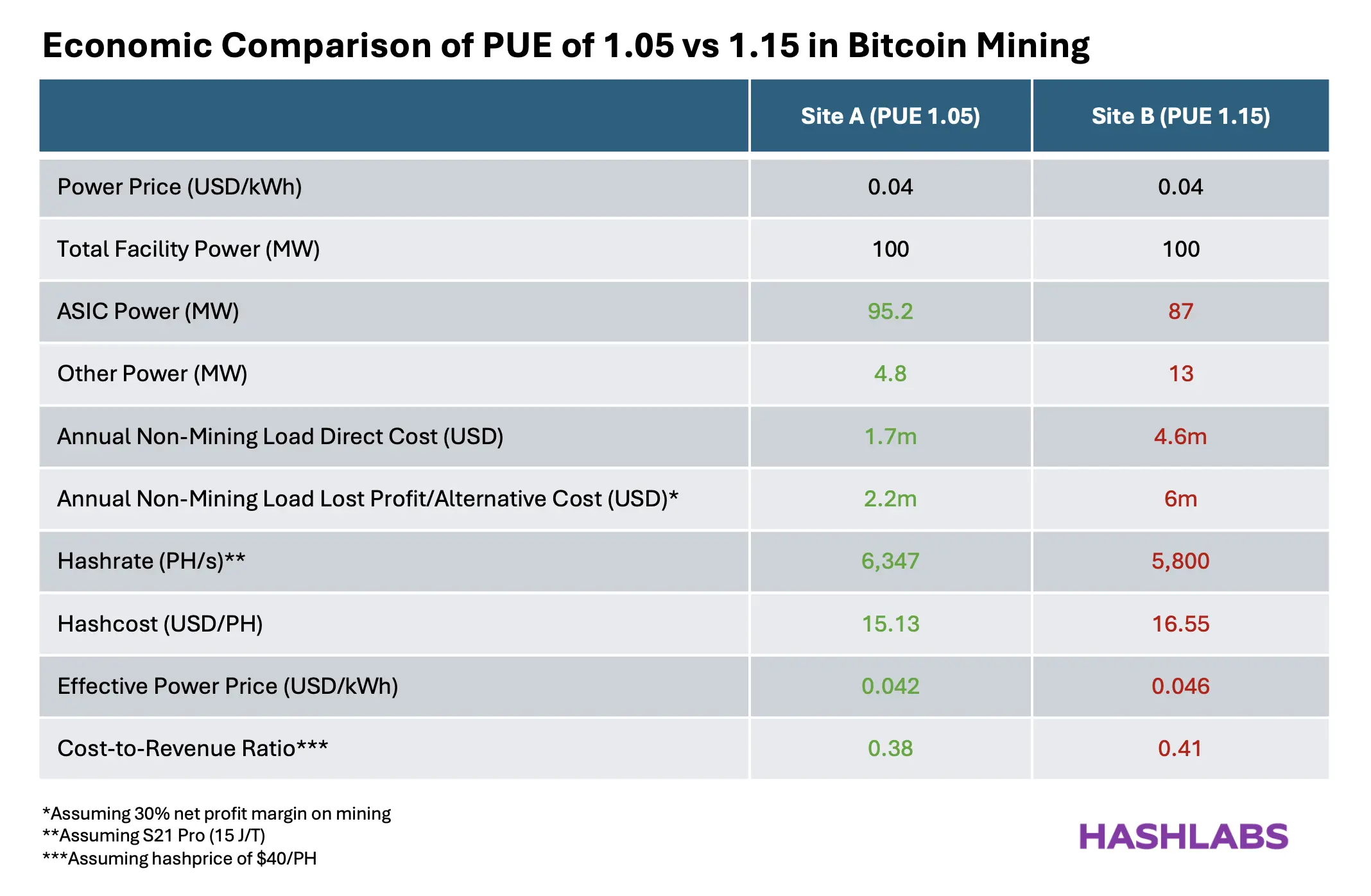

Consider two mining sites:

You might imagine Site A located in Norway with minimal cooling requirements, while Site B operates in Texas with heavy cooling demand.

Both sites have:

With a PUE of 1.05, Site A can allocate ~95.2 MW to actual mining.

With a PUE of 1.15, Site B allocates only ~87 MW to mining, with the remaining 13 MW consumed by cooling, losses, and auxiliary loads.

This difference in usable mining power has major profitability implications.

Site B spends approximately $4.6 million per year on non-mining electricity — about $2.9 million more than Site A.

If we assume a 30% net profit margin on mining operations, Site B also forgoes roughly $6 million in annual net profit due to reduced mining capacity — about $3.8 million more in lost profit than Site A.

In effect, Site A earns $3.8 million more per year purely due to lower infrastructure overhead.

This example also highlights how PUE raises the effective electricity price:

Thus, colder environments and lower PUE can offset moderately higher nominal electricity prices.

PUE becomes even more critical in power-constrained environments. When electricity is scarce, maximizing the share allocated to revenue-generating compute becomes essential — a dynamic increasingly relevant as global electrification accelerates.

Optimizing PUE primarily comes from three sources:

A key realization is that most PUE optimization decisions occur before a facility is built and energized. Once operational, improving PUE becomes far more difficult.

As discussed, cooler climates generally enable lower PUE due to reduced cooling requirements.

While no location is perfect across all variables — power price, regulation, logistics — climate remains one of the most influential drivers of infrastructure efficiency.

It should not be underestimated.

Site design decisions impact PUE — and profitability — for the entire lifespan of a facility.

Design should never be rushed. Instead, operators should:

Site design is an engineering discipline in itself. Off-the-shelf, non-tailored solutions may enable faster deployment but often result in long-term inefficiencies — particularly in cooling architecture.

These are engineering decisions, not merely budget decisions. Poor design choices are paid for over years through higher operating costs.

The first two optimization levers are largely structural and should always be maximized.

The third lever involves capital investment.

Higher-quality infrastructure improves how efficiently power is delivered to machines — reducing both cooling demand and electrical losses.

Examples include:

This represents a classical CAPEX vs OPEX tradeoff. Operators must analyze whether upfront investment yields sufficient long-term electricity savings to justify the cost.

For long-duration sites, these investments often produce strong returns.

Do not model mining economics using nameplate ASIC power alone.

Always account for infrastructure overhead. Even optimized sites typically require 3–5% additional energy beyond miner consumption.

Hot climates carry an invisible electricity penalty.

Higher cooling demand increases PUE and raises real cost per kWh.

Cheap infrastructure often means higher long-term power costs.

Lower upfront CAPEX can lock in structurally higher operating expenses.

High PUE reduces usable mining capacity.

When grid capacity is constrained, higher overhead means less power available for hashing.

Be cautious of sites where PUE is not economically prioritized.

Hosting facilities, quick-sale developments, and poorly optimized projects often lack incentives to minimize infrastructure overhead. Always request real facility power data when evaluating hosting or acquisitions.