Blog • November 18, 2025

Over the past few years, Russia has grown into one of the world’s biggest bitcoin mining countries, mostly thanks to its vast hydro and gas surplus, cold climate, and large-scale, previously under-utilized industrial power infrastructure in Siberia.

Yet, due to significant language and cultural barriers, the Russian bitcoin mining industry is often misunderstood in Western discussions. For years, it has been portrayed as a place of limitless cheap electricity and effortless expansion, but as we will explain in this article, this wild east narrative does not reflect reality anymore.

As you will learn in this report, the Russian bitcoin mining industry is currently undergoing a transformation both on the geographical and regulatory level. Miners in Russia are now facing new licensing and regulatory requirements, regional mining bans, tightening power tariffs, a strengthening ruble, and a general increased competition for electricity in the traditional bitcoin mining hubs.

Russia, an energy superpower, will always be one of the top countries for bitcoin mining. However, the growing pains the industry is currently going through means it will likely see modest growth over the next couple of years.

We wrote this report because we believe we are in a position to provide some insights on the topic, as our team includes several Russian-speaking members, including people from Russia and neighboring countries. Furthermore, being in a tight-knit and global industry, we know many Russian miners. Many Russians and people of other nationalities have provided insights to this report; some are named, while many did not want to be named.

What follows is an updated view of mining in Russia in late 2025 with, amongst others, hashrate estimation, power consumption estimation, geographical breakdown, regulatory breakdown, and power market dynamics.

Disclaimer for our banking partners: Hashlabs does not operate in Russia. We simply maintain relationships across the global mining industry. This report reflects analysis, not involvement.

As you can imagine, estimating the hashrate for any single country is an exceptionally difficult task. All historical estimates of a country’s hashrate, including the one we will come with here, must be viewed not as the definite truth, but more as a best guess.

Estimating the Russian hashrate is particularly difficult as there are no public bitcoin mining companies there and the country is just so massive geographically. As part of the new regulation, Russian industrial-scale miners must register their machines in a common database, which, theoretically could give the Russian government an overview of the industry’s size. However, the Russian government has yet to publish any credible data on the size of the industry since they set up that registry. Thus, as of now, the only thing we can do is to use the most credible estimates.

In February 2024 we last published the Hashlabs Mining Map, which placed Russia at around 12% of the global hashrate. This estimate is relatively old and the Russian mining industry has likely seen significant relative growth since then.

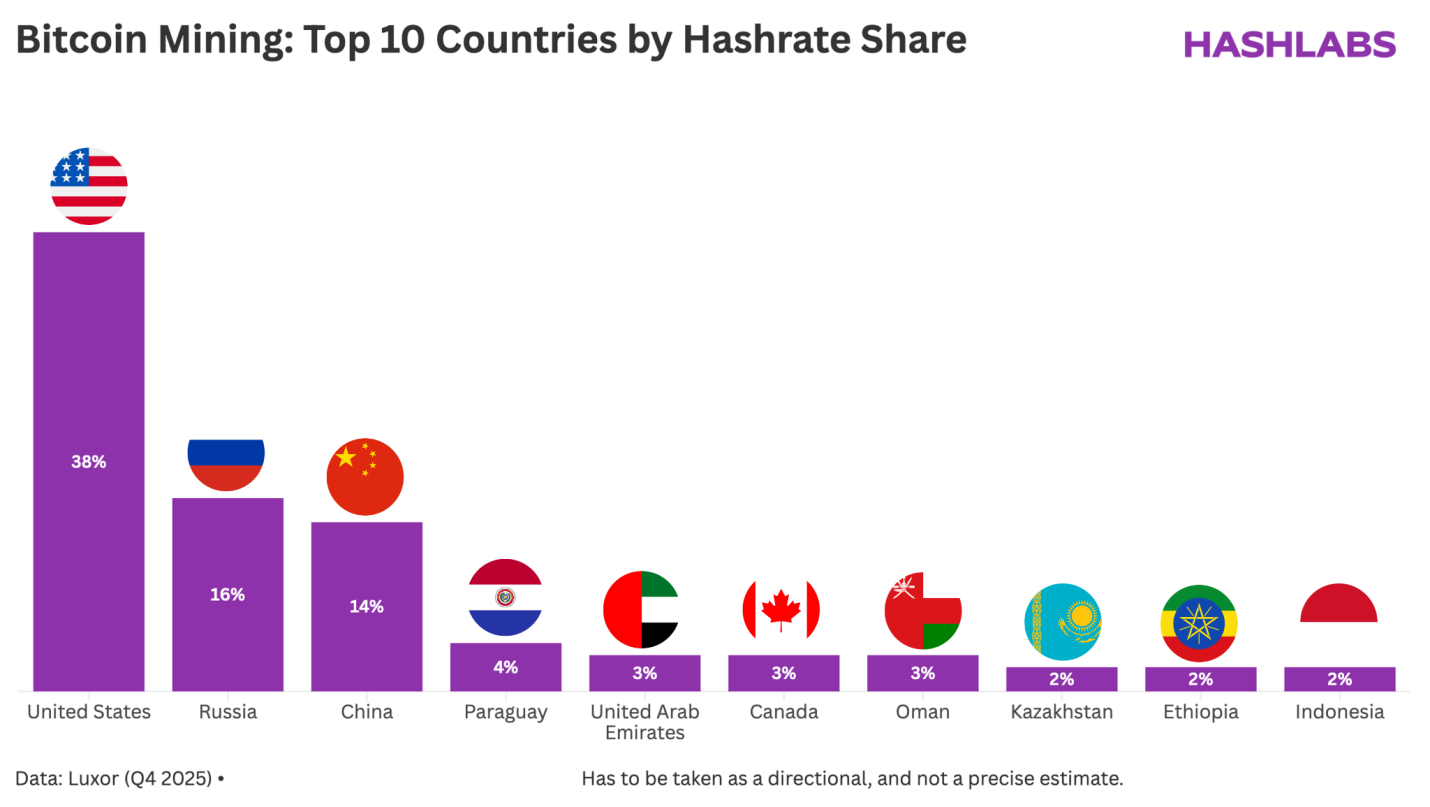

An alternative source of updated data is Luxor’s Hashrate Heatmap from Q4 2025, which places Russia closer to 16% (15.5% precisely). We believe this estimation is the most accurate and credible one at the moment.

At 16% of the global hashrate, Russia is the second-largest bitcoin mining country in the world, surrounded by the United States in first place and China in third place. The three global geopolitical superpowers are, coincidentally, also the three global bitcoin mining superpowers.

Of all the largest bitcoin mining countries in the world, Russia has likely seen the most relative growth over the past few years. We don’t have to go further back than to January 2022, when Russia’s global hashrate share was only 5%, as per Cambridge’s (CBECI) estimates.

Since January 2022, Russia’s global hashrate share has more than tripled, illustrating the massive growth and transformation of the Russian bitcoin mining industry.

However, as we will explain in the later sections of the article, Russia’s market share will likely stagnate or even shrink going forward as the industry has already entered a phase of maturity both with regards to regulation and electricity consumption.

In the next section, we will explain why, from a pure macro electricity availability perspective, it is unlikely that the Russian bitcoin mining industry will see the same explosive growth in the future as historically.

According to Cambridge, the global bitcoin mining industry currently draws around 26 GW of electricity. Assuming the Russian bitcoin miners are using machines at the average industry energy-efficiency, the Russian electricity for bitcoin mining should be approximately 4 GW.

In July 2024, Russia’s Ministry of Energy estimated the total electricity consumption of the country’s miners at approximately 16 TWh per year, which is equivalent to 1.8 GW given 100% uptime.

There is a massive divergence between our numbers and the 2024 numbers of the Russian Ministry of Energy. However, we still believe our estimate is better reflecting the current situation due to two factors. First, according to Cambridge, the global bitcoin mining electricity consumption has increased by 63% since July 2024, and it is reasonable to assume that the Russian mining industry has grown at a faster rate than the global average during this period. Second, we have to remember that the governments tend to underestimate the sizes of industries, as a lot of information is not available to them. So, we still consider 4 GW a reasonable estimate for the Russian bitcoin mining electricity consumption.

The chart below further illustrates the massive historical growth of the Russian bitcoin mining industry. As you can see, at 4 GW, the industry consumes just below 3% of the country’s electricity, up from 1.3% in July 2024 and only 0.4% in January 2022.

This chart is perhaps the most important one for analyzing the Russian bitcoin mining industry. Earlier, Russia had a significant electricity surplus in Siberian historical industrial hydro strongholds like Irkutsk and Krasnoyarsk, providing easy expansion opportunities for Russian miners. However, the industry has now grown to fill that void of electricity surplus, and is now consuming 3% of the country’s entire electricity.

Interestingly, from my historical analysis, I found that very rarely do countries spend more than 3% of their electricity on mining. We saw in historical bitcoin mining strongholds like Norway, Sweden, and Iceland, that once mining reached such a share of the domestic electricity consumption, the industry stopped growing as fast due to limited availability of new electricity connections and in some cases pushback from the government.

Thus, we view 3% of domestic electricity consumption for mining a barrier that is difficult to break through, and there might just not be much more surplus electricity left for Russian miners to grow at their historical pace. The era of limitless growth of Russian mining is over.

To further show these developments, we have created a chart showing the Russian electricity production by year all the way back to 1985. This chart clearly shows the role Russian miners have played in the Russian economy so far.

As you can see on the chart, Russia’s electricity production peaked in 1990, just one year before the Soviet Union was dissolved. The 90s were a decade of economic decline in Russia and other post-soviet countries, leading to a huge reduction in industrial production and household consumption, which again led to a massive decline in the electricity demand and production.

As further shown in the chart, the Russian electricity production only reached its post-Soviet high in 2016. This fact is even more spectacular considering that the entire world saw significant electrification in the same period. Thus, Russia had a massive void of underutilized Soviet era electric generation and transmission infrastructure that was just waiting for someone to come and use it.

Bitcoin miners played that role. They set up shop right next to this underutilized infrastructure and monetized the otherwise unused electricity. However, since 2015, particularly since 2020, there has been a quite rapid growth of Russian electricity consumption and production, and the system is not as underutilized as it was in the 90s and 2000s.

Bratsk Hydropower Station - A typical Soviet era hydropower plant.

As we will explain later in the report, Russian miners have now played a large-part of their role as monetizers of an underutilized electric grid and will shift more off-grid, particularly to natural gas that otherwise would be flared. This provides a way for Russian miners to consume energy that would otherwise be wasted, instead of just passively drawing from an increasingly crowded electric grid. The Russian mining model will see a shift toward off-grid.

In the next section, we will explain which geographic regions Russian miners have historically been operating in, and where they will move next.

Russia is a massive country with vast local diversity in climate and energy supply and demand dynamics. In Southern Siberia, where mining has historically been concentrated, there are massive hydropower resources. In the northern and western parts of Siberia, you will find huge oil and gas fields. And the northwestern part of the country has both significant nuclear, natural gas, and hydro power plants.

One of the most critical things to acknowledge when analysing the Russian bitcoin mining industry is that it is far from one unified market, but a continent-sized patchwork of local conditions.

Overall, the geography of mining in Russia can be divided into two eras. The first era was shaped by the industrial hydro clusters in Siberia, especially around Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and the captive grid of Norilsk. These eastern regions formed the original heart of Russian mining. They offered extremely low-cost electricity, mostly surplus hydropower from power plants built for Soviet aluminum production, as illustrated in the chart in the previous section. For several years, these Siberian hubs were among the most competitive mining regions in the world, attracting both domestic operators and many foreign miners.

However, the very success of these regions created new constraints. The rapid growth of mining pushed the previously underutilized power grids to their limits, similarly to what happened in Kazakhstan in 2022. The electric utilities and local authorities had to do something. The result was rate hikes, a crackdown on unlicensed “gray” mining taking advantage of subsidized electricity, seasonal curtailments in certain districts, and even year round restrictions in parts of Irkutsk.

Due to these measures, the once-abundant capacity of the southern Siberian hydro corridor is now largely saturated. While Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Norilsk remain major centers of mining today, they no longer represent the primary direction of growth.

The second era of Russian mining is unfolding further north and west, as well as directly on the country’s oil and gas extraction fields. In the Arctic regions of Murmansk and Karelia, miners are still able to find some pockets of available electricity on the grid. These regions offer the same climatic advantage as Siberia, but with more available transmission headroom and less direct local load competition.

Meanwhile, in Yamalo-Nenets and Khanty-Mansi, miners are bypassing the grid entirely by sitting directly on oil and gas fields, converting stranded or flared gas into electricity on site. This model resembles the oilfield mining seen in parts of North America, but in Russia it is unfolding across a much larger landscape with deeper industrial integration and colder average temperatures.

We have also seen a few Russian bitcoin mining companies announce partnerships with oil and gas companies, most notably Bitriver, who announced in October 2024 that their total capacity of using associated gas for bitcoin mining had surpassed 30 MW. In 2022, Bitriver signed a partnership with Gazprom Neft, Russia's third-largest oil company.

From our knowledge, there is not much flare gas mining yet in Russia, but apparently, a lot of Russian miners are now looking to get into that market.

Taken together, this marks a clear spatial transition in Russian mining. Southern Siberia is where the industry first scaled and matured, supported by hydro and legacy industrial infrastructure. The Arctic surplus regions and the western Siberian gas basins are now where growth will shift, driven by a search for new energy sources, greater regulatory stability, and the ability to operate without competing directly with local residential or commercial demand.

In the next section, we will discuss the most important driver of the coming Russian mining migration - electricity pricing.

It is important to realize that due to the vast geographical footprint, Russia’s electricity tariffs vary significantly between regions.

The biggest misconception among westerners about mining in Russia is that electricity is still dirt cheap. The reputation for ultra-low prices came from the first wave in Irkutsk and Krasnoyarsk, where miners before could tap into all-in electricity rates as low as 2 rubles (around $0.025/kWh).

As mining scaled to gigawatt levels, and the Soviet era electricity surplus was monetized, industrial tariffs were adjusted upward. Today, a large, legally connected operation in Siberia typically pays around 4.5 to 5 rubles per kWh ($0.056 to $0.062) for electricity. Hosting rates have increased too, with observed market rates at around 5.5 rubles per kWh ($0.068).

To give a real-world example, one Irkutsk hosting customer told us he paid 3.7 rub per kWh ($0.046) as late as June 2024, but in October 2025 he paid close to 6 rubles per kWh ($0.074/kWh).

Miners can also participate in time-of-use programs. One miner told us that by only running around two-thirds of the time, it is possible to get rates as low as 3.5 rubles per kWh ($0.043). However, this just confirms the story of the rate hikes - in the golden days of Russian mining, miners could achieve even lower than 3.5 rubles per kWh with 100% uptime. Now they need to sacrifice one-third of their uptime to get such, previously normal, prices.

The lowest marginal energy today is increasingly off-grid. As we explained in the previous section, in oil and gas rich regions like Yamalo-Nenets and Khanty-Mansi, miners are exploring the prospects of converting associated gas to power at the wellhead, avoiding grid tariffs and losses. Well-run projects in these basins report delivered power in the 3.0–4.0 rub/kWh range, sometimes lower, but nothing about it is plug-and-play: you finance generation, live with Arctic logistics and maintenance, align with state-controlled counterparties, and manage uptime variability that grid users do not face. It is not as easy as before, when you could just plug into the grid and get reliable electricity at sub 3 cent rates.

Currency fluctuations are also playing an important role in Russian bitcoin mining. The ruble’s strength in 2025 has further compressed margins and made Russian miners relatively less competitive. Of course, over the long-term, the ruble has depreciated against the USD, and it is reasonable to expect this long-term trend to continue.

Several operators we spoke with expect a long-run power price floor around the dollar equivalent of $0.05 to $0.06 per kWh for large-scale mining in Russia. This is a bit better than the current levels, but it is still far from the sub $0.04 prices that made Russia a bitcoin mining haven.

The rising tariffs are more than anything putting a squeeze on the competitiveness of the Russian bitcoin mining industry. As we will explain in the next section, Russian miners are also under pressure from big regulatory changes.

It is no secret that the Russian government likes to keep control. Over the past few years, it has somewhat passively witnessed the massive growth of the bitcoin mining industry. Of course, given the industry’s significant consumption of electricity, a national strategic resource, everyone expected that the government would eventually intervene.

The Russian government has recently made significant efforts to regulate the bitcoin mining industry with the goal of getting better oversight, onshoring industry capital, and improving tax collection.

In short, these regulatory changes are impacting some parts of the industry more than others. The new regulation makes it easier for more traditional financial players to be involved in the industry, but it also makes it more difficult for foreign investors, who played a large part in the Russian mining industry so far.

Here is how the regulation is playing out.

In late 2024, Russia moved bitcoin mining from a gray zone into a regulated industrial activity, with federal legislation coming into force that formally legalizes crypto mining and brings it under national oversight by various designated government bodies. The regulatory reform is built on two pillars. First, it is the legalisation under federal law, which reduces the regulatory risk for the industry players and makes it clear for the government how to behave in relation to the industry. The second pillar is the requirements for the industry, which are mainly to properly register companies and machines and pay the taxes.

In practice, the state now differentiates between miners (machine owners) and mining infrastructure operators (hosting companies). Miners and operators must register with the federal tax authorities and related ministries before connecting at scale, while individuals can still mine without joining the register so long as their electricity consumption stays within regional limits.

Supervision is tightening on the hardware side as well. In July 2025 the Ministry of Energy launched a national registry of mining equipment to help regions identify industrial activity, align it with local grid capacity, and bring output into the tax net.

Reporting obligations extend beyond registration. Under the new framework, miners must disclose mined volumes and wallet identifiers to designated authorities (with financial-monitoring access), and the government reserved discretion to restrict mining in specific territories when grids are stressed. Practically, this is why we now see territorial bans and seasonal curtailments layered on top of national legalization.

Those territorial rules are real. Starting January 1, 2025, Russia imposed six-year prohibitions on mining in a set of regions through March 15, 2031, and kept seasonal curtailments in parts of Siberia during winter peaks. Separately, Irkutsk went further: the southern part of the region banned crypto mining year-round until 2031, converting what had been a winter moratorium into a permanent measure. These moves codify what operators already felt on the ground: load growth must be steered toward surplus zones, not stressed ones.

Policy is also evolving around AI vs. crypto. Draft measures introduced in mid-2025 would bar data centers that receive subsidized power from running bitcoin mining, with the explicit intent to prioritize AI compute for those megawatts. If you thought AI is only competing for megawatts in the United States, you were wrong.

For serious players, the new regime is more predictable than the old one, and the ones we spoke with consider the risk of new, regulatory surprises as low. The new regulations make it much easier for the traditional financial institutions of Russia to enter the mining industry. At the same time, it makes it much more difficult for hosting companies to have foreign customers. Such foreign miners provided a large portion of the capital that were required to grow Russia into the second-largest mining country in the world. A lower inflow of foreign capital might lead to a slower growth of the Russian mining industry than we saw over the past few years.

Industrial mining remains concentrated among a handful of vertically-integrated operators and large hosting companies.

A BitRiver mining site in Siberia.

BitRiver is the largest historical player, operating at many Siberian sites but has begun piloting associated-gas generation sites. BitRiver has also announced a pivot to AI with the buildout of a 100 MW AI data center in Buryatia, showing that the competition for mining megawatts from the AI sector is intensifying in Russia just like in the United States. BitRiver is currently sanctioned by the U.S. government, possibly due to its ownership structure and association with Oleg Deripaska, a sanctioned Russian oligarch.

Other notable players include Intelion, BitCluster, MiningCluster, and MyRig.

Russia is still one of the most important bitcoin mining countries in the world, but the phase of effortless growth fueled by the Soviet-era electricity surplus is over. The hydropower clusters of Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Norilsk have reached maturity, tariffs have risen, and regulatory oversight has tightened. New territorial restrictions and registration requirements are formalizing the industry, making it easier for domestic institutional capital to enter, while at the same time making it harder for foreign miners and hosting businesses to operate at scale.

Going forward, growth in Russian mining will not come from cheap grid-connected hydro. It will come from off-grid energy, particularly associated gas in West Siberia, where miners can produce power directly at the source rather than competing with residential and industrial consumers on the grid. This shift requires deeper industrial capabilities, larger capital commitments, and alignment with state-controlled energy firms. It is no longer a frontier market for opportunistic foreign miners — it is becoming a strategic domestic sector.

For the global mining landscape, this matters. If the United States is increasingly constrained by competition from AI data centers, and Russia is entering a slower phase characterised by regulation and electricity constraints, then the next significant step-change in global hashrate will need to come from new frontiers — regions with stranded hydro, flare gas, and large-scale generation that remains underutilized. Those regions exist, but they are fewer than many believe.

Russia will remain a top mining country. But its role is shifting from hyper-growth to consolidation and industrial integration. The wild east era is over.